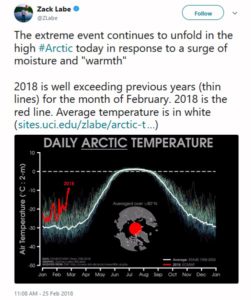

The North Pole saw record high temperatures for February during 2018.

Reuters reported:

Temperatures may have soared as high as 35 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) at the pole, according to the U.S. Global Forecast System model. While there are no direct measurements of temperature there, Zack Labe, a climate scientist working on his PhD at the University of California at Irvine, confirmed that several independent analyses showed “it was very close to freezing,” which is more than 50 degrees (30 degrees Celsius) above normal.

The warm intrusion penetrated right through the heart of the Central Arctic, Labe said. The temperature averaged for the entire region north of 80 degrees latitude spiked to its highest level ever recorded in February. The average temperature was more than 36 degrees (20 degrees Celsius) above normal. “No other warm intrusions were very close to this,” Labe said in an interview, describing a data set maintained by the Danish Meteorological Institute that dates back to 1958. “I was taken by surprise how expansive this warm intrusion was.”

Climate scientist Sidd Mukherjee added, “Yes. Even more scarily — the fast ice north of Greenland is gone. That was some of the oldest ice left. It hasn’t melted, just been blown away and drifted away with the currents.” (see “Talk about unprecedented“)

An article in Rolling Stone about climate migrations quotes Solomon Hsiang:

Hsiang has many good papers outAn article in Rolling Stone about climate migrations quotes Solomon Hsiang:

“Most people don’t realize how much climate affects everything, from their property values to how hard people work,” says Solomon Hsiang, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, who led a recent study that predicts, as the climate warms, there will be “a large transfer of value northward and westward.” And the wealthy, who can afford to adapt, will benefit, while the poor, who will likely be left behind, will suffer. “If we continue on the current path,” Hsiang says, “our analysis suggests that climate change may result in the largest transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in the country’s history.”

Dr. Mukherjee replied, “But for city officials in at-risk cities, homeowners like Brown are terrifying. “Once people start thinking about the long-term value of their homes and how they will be impacted by climate change, that changes the game completely,” a county attorney in Florida says. What happens to the value of a house in, for instance, Fort Lauderdale, when the cost of flood insurance triples? “When I think about the future of South Florida, it’s flood insurance that scares me the most,” Wayne Pathman, a prominent Miami lawyer and board member of Miami Beach’s chamber of commerce, tells me. Many officials fear a climate-driven exodus that pushes down property values, which in turn reduces property-tax revenues, which are central to funding city services like police and teachers, not to mention road repair and infrastructure maintenance, at precisely the moment when the city needs to spend more to adapt to climate change.

Flooding in downtown Miami after Hurricane Irma in September 2017. Kadir van Lohuizen/NOOR/Redux

It’s a downward spiral for real estate that’s very hard to reverse. “It’s just like the dynamic in the stock market,” says U.C. Berkeley’s Hsiang. “The longer you hold on, the more you have to lose.” And, in many cases, the regions of the country where climate-change denial is strongest, such as the Southeast, are exactly the regions where residents have the most to lose. “In many places, climate denial is going to turn out to have big economic consequences,” Hsiang says.

[Hsiang has many good papers out]